Northern Nigeria, a region steeped in tradition and customs, has grappled with a vexing issue that gnaws at the heart of public health and environmental welfare: open defecation. Two northern states: Bauchi and Jigawa have stood at the forefront; their proximity and cultural uniqueness exacerbating the challenge. The health perils and ecological hazards spawned by this practice raised alarm bells in the corridors of governance, propelling both states to wage an unyielding battle against this menace.

A beacon of hope emerged from the midst of adversity. Jigawa State, with its renewed determination, secured a remarkable validation: certification as Open Defecation Free (ODF) by esteemed bodies such as UNICEF and other global health watchdogs. The ripples of this achievement have been felt even in neighboring Bauchi State, as it aspires to emulate Jigawa’s triumph over this age-old scourge.

Bauchi State’s Ongoing Struggle to Achieve Open Defecation Free Status

Amidst repeated assertions by authorities that Bauchi State is diligently working to eradicate open defecation, the reality paints a different picture. Communities once declared Open Defecation Free (ODF) are regressing, casting doubt on the effectiveness of the measures taken. Despite the existence of bye-laws meant to curb the practice, their enforcement remains lax, explaining the challenges of behavior change beyond mere media campaigns.

Samuel Zakka, a Sanitarian Officer at Bauchi State’s RUWASSA, acknowledges that while seven local government areas (LGA’s) have achieved ODF certification, the state’s approach has impacted the pace of progress. Unlike other areas where external support plays a greater role, Bauchi emphasizes self-sufficiency, leading to slower advancement. Communities, in this model, are tasked with providing their own toilets, an undertaking many struggle to afford.

For certification, each household must possess a toilet, and the community must be devoid of open defecation. This stringent criterion contributes to the gradual pace. Despite the challenges, Zakka believes Bauchi’s progress surpasses that of other states. Dass, Bogoro, Toro, Shira, Gamawa, Ganjuwa, and Tafawa Balewa LGAs have obtained ODF certification. Katagum LGA’s certification is in progress, awaiting the nod from the Federal Ministry of Water Resources and donor agencies.

In contrast to Jigawa State, where government funds the program post-donor support, Bauchi’s model is a blend. Donors contribute 70% of the funds, while the state allocates 30%. This funding discrepancy potentially hampers progress.

The delay, Zakka explains, results from donors’ sequential approach, picking a few LGAs at a time. The state government’s financial model is a partnership to maintain sustainability and oversight, demonstrating commitment.

Changing people’s behavior requires time. The process of triggering, followed by community education, often delays momentum. Zakka acknowledges the assistance of traditional authorities, whose cooperation has eased the campaign. This cautious pace, Zakka assures, is to ensure a thorough and complete transition.

Ahead Of Inauguration: Tinubu Makes Changes, Reassigns Oyetola, Tunji-Ojo, Momoh, Others

a

Enacting bye-laws is insufficient without active enforcement. While laws exist in certified LGAs, their implementation falls under local government jurisdiction. Zakka clarifies that RUWASSA’s role is to support these laws as a signatory, not enforce them.

While challenges exist, Zakka emphasizes that cooperation with donors and microfinance institutions has been instrumental. Bauchi’s strategy involves financing these institutions, linked with Toilet Business Owners who construct toilets for households on loan.

Ezekiel Sukumun of Rahama Women Development Centre echoes Bauchi’s approach, emphasizing a behavioral-centered model and involving traditional leaders. He asserts that fines alone can’t change behavior; instead, a mix of approaches is vital.

Bauchi’s journey towards ODF is marked by both achievements and challenges. The state’s unique approach, while gradual, aims to foster self-sufficiency and long-term sustainability in curbing open defecation. The intricate interplay of community involvement, donor support, and governance reveals the complexity of this endeavor.

Jigawa’s success story

However, Jigawa’s journey to ODF status was far from a seamless narrative. It unfolded as a chronicle of commitment, resilience, and a dance with cultural resistance. Engr. Labaran Adamu, the resolute helmsman of Jigawa State Rural Water, Sanitation and Supply Agency (RUWASSA), recounted how this milestone was etched not only with sweat and toil but with the relentless backing of the State Governor.

Amidst the early chapters of the campaign against open defecation, Adamu revealed that a catalyst lay within the folds of funding coupled with the commitment of the state government. The Governor’s steadfast devotion cast a luminous thread through the tapestry of this narrative, shaping the course of events that unfolded. “Our journey towards eradicating open defecation was not a solitary endeavor; it was the harmony of collective efforts,” Adamu emphasized.

The governor, described as a sentinel of progress, stirred the winds of change. He rallied his First Class Emirs, orchestrating a symphony of support that resonated across nook and crannies of the state. A resolute proclamation was issued: the abandonment of open defecation. The Commissioner of Water Resources was summoned to orchestrate a triumphant chorus involving traditional leaders and stakeholders. Adamu argued, “Our governor was not a mere spectator; he was the conductor, the driving force behind our triumph.”

Harnessing the voices of religious, community, and traditional leaders became a cornerstone of success. These figures wielded their influence as a mighty cudgel, piercing through cultural inertia. Even security agencies stood shoulder to shoulder, fortifying the mission. Adamu acknowledged, “Our engagement with these leaders was a conduit of change. Their resonance seeped into every corner, unfurling the flag of transformation.”

Yet, the path wasn’t strewn with rose petals; thorns of resistance pricked their journey. The tendrils of tradition gripped some communities tightly, considering open defecation a beacon of prosperity rather than peril. Adamu shared the tale of their struggle, revealing the tenacity of those who clung to these customs. Only through a ballet of persuasion, guided by religious leaders and fortified with daily sermons, did the scales finally tip towards acceptance.

With vivid anecdotes, Adamu illuminated the transformative power of their campaign. He spoke of an elderly man who had never once used a toilet, swayed by the steady drip of enlightenment. Adamu recounted stories of resilient communities, fortified by the nurturing words of their leaders, dismantling the shackles of custom for the promise of sanitation.

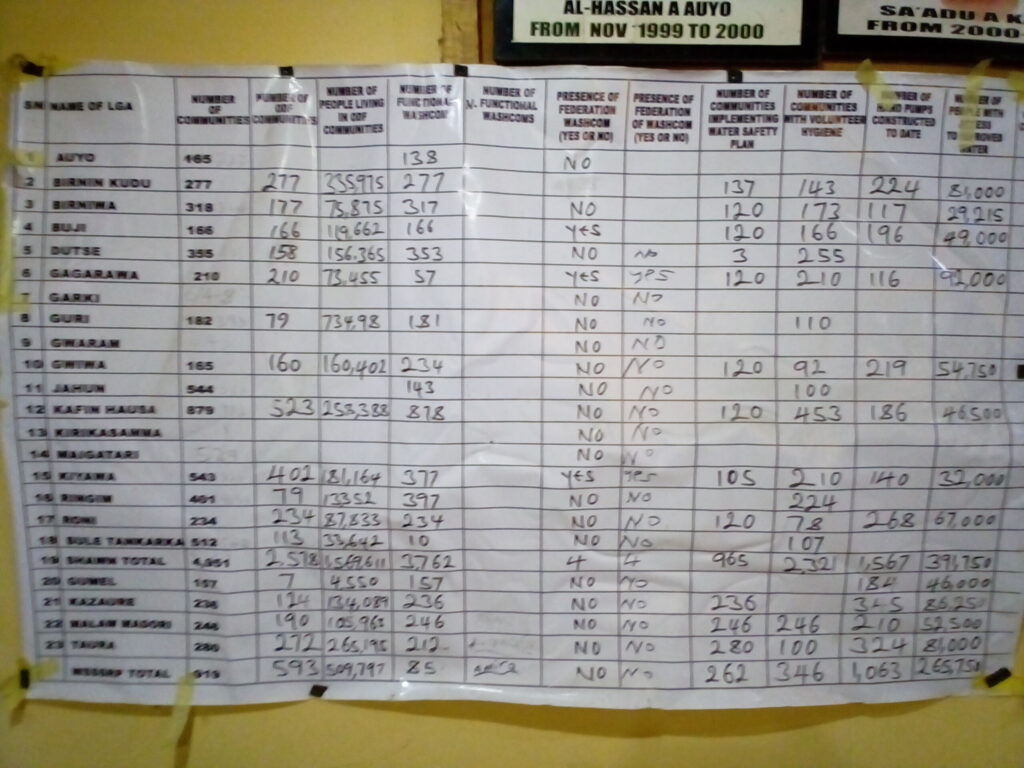

The campaign, however, demanded more than just rhetoric. It necessitated the sweat of commitment and the ink of financial investment. Engr. Labaran Adamu illuminated the financial landscape, revealing the struggle for funding against a backdrop of patience and persistence. Triumphs, like that of Birnin Kudu, underscored the importance of involving traditional rulers, creating a synergy that paved the way for success.

Reshaping Habits: A Battle Against Tradition

“Changing traditional practices isn’t a simple feat,” locals assert, recounting the arduous journey of shifting from age-old ways of relieving oneself to the modern approach. This transformation, though fraught with resistance, has been steered by the resolution of religious and community leaders who wielded gradual change as their weapon, successfully liberating communities from the clutches of open defecation.

Malam Hussani, a resident of Babaldu in Birnin Kudu local government, reflects on his own struggle to sway family and friends away from open defecation. His endeavor was marked by setbacks, requiring persistent efforts to convince his close ones. Despite advocating the hazards to health and human life, the transition faced reluctance. The gradual efforts to foster change eventually took root, relegating open defecation to history. Before, Hussani recalls streets marred by the presence of human waste, a sight that induced discomfort and tarnished community gatherings. “Our traditional rulers were called to Birnin Kudu,” he narrates, “and through places of worship, the village received the message of the hazards.”

For Malam Awaisu Badamasi, a religious leader in Sabon Gida of Bamaina, the path was smoother. He found his people open to change, embracing toilet usage after gentle enlightenment. Even children, under Awaisu’s guidance, adhered to a practice of digging and burying their waste. “Our people trust everything we tell them,” he emphasizes, attributing the successful transition to the community’s willingness to adapt.

This journey from old to new traverses diverse landscapes. Kabiru Yau Bammuwa, in his observations, sheds light on the polygamous structure of his village, where open defecation was rampant. Such habits sowed the seeds of disease outbreaks. Yet, as the government’s intervention began to bear fruit, attitudes transformed. With the advent of toilets, communal hygiene improved, unraveling the connection between poor sanitation and disease.

Amidst these tales of transformation, challenges lingered. The lack of western civilization among mothers, according to Abubakar Abdullahi, fanned the flames of open defecation. Ignorance perpetuated the practice, but gradually, education and awareness initiatives turned the tide.

Jigawa’s tale of transition wasn’t a solitary one. Religious and community leaders played significant roles. As they marched door to door, sanitation campaigners triggered conversations, enlightening one household at a time. The voices of these leaders echoed through mosques, public gatherings, and even schools, propagating a hygiene-conscious way of life.

Ahmed Sule, a vigilant youth leader, carried the torch further. Engaging his village, Mariri, he rallied his people to adopt change. The momentum spread from village to village, leveraging traditional and religious forums. By imbuing their messages with religious significance, the campaign found receptive ears.

Ahmed Idris, WASH Coordinator in Birnin Kudu, highlighted the multifaceted strategies employed. He emphasized community involvement through committees, sparking change from within. From triggering discussions to encouraging contributions for toilet construction, the journey unfolded in stages. He shared the tale of Gidan Darge, a village that ventured beyond household toilets, erecting public facilities to be shared by all.

The journey to Open Defecation Free status came with sleepless nights, efforts amplified amidst rainy and sunny days. Sacrifices formed the bedrock of success, as each community bore witness to the transformation. Fish vendors found relief from swarming flies, a testament to the newfound cleanliness. In this odyssey from entrenched habits to emerging practices, the steady, persistent guidance of community and religious leaders stands as the beacon that guided the way.

The implementation of by-laws banning open defecation marked a defining chapter in their story. Jigawa State etched its commitment into law, echoed by other local governments, and enforced by security agencies. The symphony of change had reached a crescendo, conducted by the resonance of regulations.

Yet, their journey was not a solitary march. Development partners like UNICEF, USAID, EU, and Partners for Development joined their crusade, lending financial and technical support. These allies bore witness to the state’s commitment, further fueling their dedication.

From the echoes of Birnin Kudu to the symphony of transformation orchestrated by religious leaders, Jigawa’s tale unveils the power of collaboration, resilience, and leadership in reshaping cultural norms. It stands as a beacon, illuminating the path for Bauchi State to traverse, as the two states script a tale of banished taboos and reclaimed health.

Adamu Yawale contributed to this reporting!

This publication is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.